- Home

- Artist

- Andy Warhol (98)

- Banksy (341)

- Chuck Sperry (15)

- Cocomilla (27)

- Damien Hirst (84)

- Dface (22)

- Invader (30)

- Kaws (52)

- Keith Haring (30)

- Laurent Durieux (24)

- Martin Whatson (30)

- Modern & Luxury (21)

- Pablo Picasso (63)

- Roy Lichtenstein (19)

- Shepard Fairey (92)

- Space Invader (22)

- Takashi Murakami (48)

- Thomas Kinkade (25)

- Tyler Stout (16)

- Unknown (144)

- Other (3702)

- Framing

- Item Length

- Signed By

- Size

- 152x102cm (60x40in) (15)

- 24 X 16 Inch (157)

- 36 X 24 Inch (12)

- 36x54 Inch Canf (9)

- 48 X 72 Inch Canf (20)

- 50cm X 70cm (49)

- 50x70cm (9)

- 54\ (10)

- 70x50cm (9)

- Extra Large (31)

- Large (122)

- Large (up To 60in.) (115)

- Massive 40\ (15)

- Medium (133)

- Medium (up To 36in.) (663)

- Small (32)

- Small (up To 12in.) (89)

- Small, Medium, Large (7)

- Various (58)

- Various Sizes (19)

- Other (3331)

- Unit Of Sale

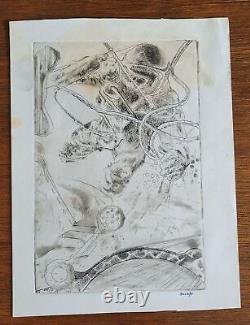

Gay Nyc Queer Juan Boza Sanchez Cuban Artist Etching Signed Dated 1981

JUAN BOZA ETCHING FROM 12981 MEASURING APPROX. IMATELY 7 3/4 X 10 1/4 INCHES IN FAIR SHAPE.

Boza was born in Camaguey, Cuba in 1941. He was a gay Afro Cuban artist specializing in painting, drawing, engraving and graphic design. His prints are fluid and confident.

He moved to Havana in 1959 in order to study at San Alejandro. He was expelled from San Alejandro due to "political issues" and became a lithographer in 1965. Boza was fired as a result of the Congress of Education and Culture which convened in 1971 and led to the censorship of many artists in Cuba. In the years between 1971 and his exodus from Cuba in 1980 Boza restored religious statues to earn a living. In 1980 Juan Boza managed to escape Cuba to New York via the Mariel boatlift.

Boza described New York as a "tremendous shock" and upon arriving in New York had to re-build Juan Boza from scratch. Boza began developing an Afro-Cuban theme that he realized was part of his culture after leaving Cuba. According to Jaun Boza, There is no distinction between my faith and my aesthetics. Juan Boza Sanchez died in NYC in 1991. It will probably strike the majority of casual visitors as just another multicultural melange.

Those who recognize that every piece in the show has a religious basis may still find it confusing, expressed in codes that only the knowledgeable can decipher. This is partly because there's little information on the Santería available in the gallery. Signage is minimal, and the catalog for the show curated by Marc Zuver of the Fondo del Sol in Washington, D. Where it originated isn't yet available.Then again, religious or mythic art is often presented without explanation. It's considered "obvious" - but that's true only for those who already understand.

Santa Claus, for instance - the immortal reindeer-powered deity shouting "Ho Ho Ho" as he enters locked houses through chimneys - must seem mighty puzzling to the uninitiated. Another reason Santería art may seem obscure is that it's deliberately encrypted.

Lecumí, a Cuban synonym for Santería, is also another word for Yoruba, the West African source of religious traditions in South America, the West Indies and the United States brought to the New World through centuries of Atlantic slave trade. Though the Yoruba were forced to conceal their beliefs, they found parallels between their theology and that of Roman Catholicism that enabled them to reconcile the two, paying homage in artwork that seemed Catholic to the untrained eye. They believe in a supreme deity who is rarely worshipped directly. Aspects known as Orishas mediate between humans and the supreme creator. Many Orishas (there are around 40) are thought to have been incarnated as humans. It's not hard to merge the Orishas with the Catholic pantheon of saints. African-descended artists did just that, to the point of introducing Yoruban symbolism into art that appears to be completely Christian. Even the cry of "Babalú-Ayé" uttered by Ricky Ricardo on I Love Lucy invokes the Orisha who controls diseases, including, today, AIDS. How many visitors to the Bride will realize that an image of Our Lady of Charity, the patron saint of Cuba (slightly mistitled in the show, it should be Nuestra Señorita del Cobre) by Cuban-born Jorge Pardo is an Orisha? The melodramatic picture is executed in parallel strokes of oil stick on a black ground. Three men huddled in a small, storm-tossed boat look prayerfully to a majestic representation of the Madonna.She is Oshun, gracious Orisha of the Oshun River, fertility, love, healing, beauty and generosity. Even the cry of "Babalú-Ayé" uttered by Ricky Ricardo on I Love Lucy invokesthe Orisha who controls diseases. Perhaps an oblique reason for the obscurity of Santería art is the aversion many non-believers feel for animal sacrifice, which is considered the most intimate contact between humans and Orishas. Drips of red paint, particularly in Osvaldo Mesa's large installation After the Ceremony reference this practice.

Even some scholarly studies gloss over the purpose and details of sacrifice, yet it ought to be discussed because it causes a popular confusion of Santería with some sort of Satanism. Santería or Lecumí is a legitimate and ancient religion, which is why, in most places, believers are legally permitted to sacrifice animals like roosters. When you go to the Painted Bride, ascend immediately to the upstairs gallery where Boza's work is displayed.

Signage there tells about his life. In Cuba he was persecuted and sent to a reeducation camp. The Mariel boatlift (1980) was a painful farewell to family and friends, yet he sought it For the Freedom to be Black, the Freedom to be a Santero (priest of Santería), the Freedom to be Gay. Boza's prints are fluid and confident. Cara/Head, studded with nails like an African sculpture, has a grimacing mouth and cowrie shells for eyes. It represents a commonly misunderstood Orisha, Elegua (Elegba), ruler of the crossroads.Elegua is present when humans choose their destinies before birth. He rewards and punishes and can be mischievous. Sometimes incorrectly equated with the Christian idea of Satan, he is not intrinsically evil and can reward good behavior. Boza's 1983 traditional painting Santa Barbara/Shango conflates the iconography of Santa Barbara (martyred by her father who was punished by being struck by lightning) with the iconography of Shango (the dynamic male Orisha of lightning, fire, water and social justice). Boza's were influential, though they're remembered only through photographs.

One pictured in the show (probably devoted to Olokun, an Orisha of uncertain gender associated with the depths of the ocean) is a baldachin of blue fabric hung with silhouettes of fishes. Boza's large painting Secret Language (1989-90) - a branching, surreal form that looks like an ideogram - is pivotal to the show. The image is repeated in the background of a small work downstairs, "Raquelin, Ana y Juan" by Maria Lino. ; Raquelin Mendieta, Ana's sister, who has taken up her work; and Juan Boza. The three crouch naked around a female silhouette.It resembles Ana's works, as well as traditional Orisha images. This piece, like others downstairs, centers on Boza as a nexus of Santería art. He's represented by one small print.

Ana Mendieta has one tiny drawing. Three unattributed masks illustrate the lively spirit of Yoruba.Raquelin Mendieta is showing a beautiful installation, Last Crossing, of white and beige sand with white sand dollars and a container of blue-tinted water suspended above a starfish. Ricardo Viera's small altar, Chango de Todos - Homage to All, Homage to Juan Boza, is a small platform in a square of earth. Metal knives tied with a strip of red fabric invoke Shango (Chango). Boza was a babalao (high priest) of Shango. The 14 artists in the show incorporate many ideas not discussed here.

One reason Santería has produced so much art is that the Yoruba believe human beings were created as objects of art. Orishas love art, and making it is a religious act. Juan Boza is a Cuban artist living in exile in New York.

Boza was born in Camagüey, Cuba in 1941 and moved to Havana in 1959 in order to study at Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes "San Alejandro". He was expelled from San Alejandro due to "political issues" and became a lithographer with the Experimental Graphic Workshop in 1965.

Boza began developing an Afro-Cuban theme that he realized was part of his culture after leaving Cuba, as well as his participation in the Santería (also known as Lukumí) religion. 1983 Award in Drawing from the Jaun Miro Foundation in Barcelona, Spain. 1981 Jerome Foundation, New York. 1967 Premio Casa de las Américas, La Habana. 1966 Exhibición Nacional de la Habana. 2003 The Judith Rothschild Foundation Grant Recipient. Juan Boza Sánchez or Juan Stopper Sanchez (1941 in Camagüey, Cuba - March 5, 1991 in New York City, New York) was a gay[1] Afro-Cuban-American artist specializing at painting, drawing, engraving, installation and graphic design. Boza studied at the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes "San Alejandro" from 1960 to 1962 and then from 1962 to 1964 at the Escuela Nacional de Arte (ENA) both located in Havana, Cuba. Boza began developing an Afro-Cuban theme that he realized was part of his culture after leaving Cuba, as well as his participation in the Santeria (also known as Lukumí) religion. He lived in New York City from 1980, when he arrived during the Mariel boatlift until his death, at Brooklyn Memorial Hospital, working at the Printmaking Workshop, the Lower Eastside Printshop and the Art Student League. In 1964, Sanchez presented a personal exhibition in the Galería Provincial de Camagüey in Cuba.Four years later, he created "Stopper: Gouaches, Drawings and Lithographies, " shown at the Gallery of Havana. In 1983, Sanchez exhibited "Juan Stopper: Black Mysticism" at the Latin Inter-American Gallery in New York. In 1984, his art was exhibited at the Museum of African Americans in Buffalo, New York. In 1990, he presented "Juan Boza's World" at the Ollantay Gallery in New York.

Sanchez also participated in many collective exhibits. He first group showing was in the 1960 Freedom for Siqueiros at the Seguro Médico Building in Havana. In 1970, he exhibited pieces in Salón 70 at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Havana; in 25 Latin American Engravings at the Gallery Pablo Picasso in Mexico; and in the Fourth American Biennial of the Engraving in Santiago, Chile. In 1975, he participated in the Ninth International Print Biennial at the Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo, Japan. In 1984, he appeared in the Third Latin American Graphic Art Biennial. 1964 - Galería Provincial de Camagüey, Cuba. Gouaches, dibujos y Litografías, Galería de La Habana, Havana, Cuba. Black Mysticism, Inter-Latin American Gallery, New York City. 1984 - Museum of African Americans, Buffalo, New York.1990 - "Juan Boza's World" in Ollantay Gallery, New York City. 1991 - Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, Illinois.

1960 - "Libertad para Siqueiros", Edificio Seguro Médico, Havana, Cuba. 1970 - "Salón 70", Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de La Habana, Havana, Cuba. 1970 - "25 Grabados Latinoamericanos", Galería Pablo Picasso, Mexico City, Mexico.

1970 - IV Bienal Americana del Grabado, Santiago de Chile, Chile. 1975 - 9th International Print Biennial, Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, Japan. 1984 - Third Latin American Graphic Art Biennial. In 1967 at the Latin American Gallery in Casa de Las Américas in Havana, Sanchez won the Portinari Prize in Lithography for his Exhibition of Havana. 1967 - Premio Portinari en Litografía - "Exposición de La Habana 1967", Galería Latinoamericana, Casa de las Américas (Havana), Havana, Cuba.

1968 - Premio - "Salón Nacional de Dibujo 1967", Galería de La Habana, Havana, Cuba. 1983 - Cintas for Art - Cintas Foundation Fellowship, New York City. 1983 - Award in Drawing from the Jaun Miro Foundation in Barcelona, Spain. 1985 - Cintas for Art - Cintas Foundation Fellowship, New York City. 2003 - The Judith Rothschild Foundation Grant Recipient. This item is in the category "Art\Art Prints". The seller is "memorabilia111" and is located in this country: US. This item can be shipped to United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Denmark, Romania, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Finland, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Estonia, Australia, Greece, Portugal, Cyprus, Slovenia, Japan, Sweden, Korea, South, Indonesia, Taiwan, South Africa, Thailand, Belgium, France, Hong Kong, Ireland, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria, Bahamas, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Norway, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, Croatia, Republic of, Malaysia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Panama, Trinidad and Tobago, Guatemala, Honduras, Jamaica, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Kitts-Nevis, Saint Lucia, Montserrat, Turks and Caicos Islands, Barbados, Bangladesh, Bermuda, Brunei Darussalam, Bolivia, Ecuador, Egypt, French Guiana, Guernsey, Gibraltar, Guadeloupe, Iceland, Jersey, Jordan, Cambodia, Cayman Islands, Liechtenstein, Sri Lanka, Luxembourg, Monaco, Macau, Martinique, Maldives, Nicaragua, Oman, Peru, Pakistan, Paraguay, Reunion, Vietnam, Uruguay.- Production Technique: Etching

- Style: Cuban

- Type: Print

- Subject: New York

- Year of Production: 1981